Who owns the (aircraft) engine(s)? The doctrine of accession explained

While the Kingdom of the Netherlands has not adopted the Cape Town Convention, Patrick Honnebier writes that the rulings of its Supreme Court indicate that this treaty determines that aircraft engines can be financed separately in this jurisdiction

The aim of this article is to discuss the issues in aircraft engines financing that arise under the provisions of the international treaties and the laws of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Recently the Supreme Court of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (the Kingdom) declared that the drafts of the international commercial conventions can fill the gaps in the existing laws. It does not matter whether or not the treaties have been ratified. The Court’s rulings are also valid in relation to the ‘Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment’ (Convention) and the ‘Aircraft Equipment Protocol’ (Protocol) which were realised in Cape Town in 2001. While the Kingdom has not yet adopted these treaties, it is submitted that they are the Supreme Court’s proper source of law to decide the issues regarding the international financing of aircraft engines. The Kingdom of the Netherlands consists of: the Netherlands, Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles. The three jurisdictions are autonomous and they have their own aviation finance laws. To a large extent, however, the relevant laws are identical. The Supreme Court decisions are of paramount significance in the three constituent states and of considerable importance to the international aviation finance world.

The aircraft engines financing industry is inherently international. However, the legal implications of a cross-border transaction are not always correctly understood and the fundamental legal differences between the two existing aviation finance treaties are not properly appreciated. On the one hand the creation, validity and effects of the sale of and the international interests in aircraft equipment are regulated in the Cape Town Convention and Protocol. These instruments provide for a modern international property law regime. On the other hand only the recognition of some rights is addressed in the ‘Convention on the international recognition of rights in aircraft’ (Geneva Convention, 1948). This is basically an outdated and inadequate conflict of laws treaty. However, several lawyers do not comprehend the differing legal objectives of the two treaties. This has led to existing misunderstandings in the international aviation practice. More specifically, at the universal level there is much debate among lawyers as to whether or not the ownership of a leased engine is transferred to the owner of the aircraft when the former object is installed on the latter. This legal principle is called the “doctrine of accession”. Referring to this theory other terms are accretion, title-shift, title-transfer and title-annexation which are variably used in this publication. In the 1990s the international engines dispute was initiated by some publications suggesting that the accession theory applies to aviation financing transactions in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Accordingly, there is no assurance as to whether or not the rights of the owners and financiers of engines are guaranteed in this jurisdiction. An additional problem is that engines are generally financed by means of cross-border arrangements. Moreover, groups of airlines have entered into a variety of international engine-pooling agreements and some of the arrangements have strong connections with Dutch airlines. The benefits which these agreements aim to bestow on the financiers and carriers are often frustrated by the negative impact of the alleged Dutch accretion theory.

At the outset it must be observed that this article does not agree that the accession doctrine is applicable to the financing of engines in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. To the contrary, it is argued below that this controversial view is not substantiated by underlying national and international laws and that the Convention and Protocol determine that no annexation of engines takes place in the Kingdom.

At present the value of one aircraft engine can run up to more than $20m [For the availability of the various types and prices of engines and aircraft, see issues of Airline Fleet Management.] As substantial funds are needed, it is customary that engines are internationally financed separately from airframes. When an engine is removed for overhaul, it is often replaced by a spare engine and the engine is often not re-installed on the same airframe. To avoid substantial expenses co-operating airlines enter into engine-pooling arrangements. As a result of the extremely movable nature of aircraft engines, generally several jurisdictions are involved in these agreements. Therefore, these transactions raise a number of questions concerning the changing legal status of an engine at the global level. These matters are of immediate concern to the owners of the aircraft and engines.

The frivolous notion concerning the title-shift of engines

For many years some Dutch aviation lawyers have suggested that the doctrine of accession applies to the financing of aircraft engines in the Kingdom. Without properly scrutinizing the validity of this view, several foreign lawyers passed it on to their clients abroad. This has resulted in the devastating impact of the title-shift theory on the universal aviation practice. The accession doctrine implies that an engine which is attached to an aircraft legally turns into a “component part” of an aircraft. It has been alleged that the sole requirement for becoming a component part is a mechanical connection. Thus the owner of the aircraft is supposed to be the owner of the engine. The suggested transfer of title to engines occurs by operation of law. This term expresses that the title-shift requires no consent of the owner of the engine. The accretion principle would make the separate financing and leasing of engines impossible.

Some Dutch lawyers even suggest that XVI of the Geneva Convention dictates a strict accretion-rule. However, this assumption is in conflict with the practical intent and legal structure of this treaty. While it aims to facilitate the international financing of aircraft, the alleged title-annexation theory frustrates its goal. Moreover, it does not provide for a property laws regime governing the creation, validity, and effects of rights in aircraft. It merely obliges its Contracting States to recognise four types of consensual rights in aircraft. From the outset it is stressed that the Geneva Convention does not purport to say whether or not the non-consensual ownership of an aircraft engine has been transferred to the owner of an airframe. Thus, the support of the Dutch lawyers to the accession doctrine derives solely from a non-existent international property law regime. Their frivolous opinion should be dismissed.

On the other hand, the Cape Town Convention and Protocol have established the needed substantive property laws. Their combined regime governs the creation, validity and effects of international interests in aircraft engines. The two instruments have codified the prevailing legal opinion of the international aviation practice. The Protocol explicitly ensures that the registered international interest in an engine shall not be affected by its installation on or removal from an aircraft. In sum, there is no existing international aviation finance treaty which dictates that the accretion principle must be observed.

The grave consequences of the alleged title-shift theory

It has been wrongfully proposed that the accession doctrine is applicable to engines financing in the Kingdom and globally. On the other hand, the same commentators that proposed this have accurately portrayed the negative practical consequences of this legal theory as follows:

“Any lawyer involved in aircraft finance transactions will be able to tell you juicy stories of security rights which are doomed, judgments which are likely to be unenforceable in other jurisdictions and third party rights which may render a hundred-page contract useless”.

“The various scenarios [concerning engines financing] discussed above invariably describe a lawyer’s paradise which is, as we all know, synonymous to a client’s depression”

“Security rights on engines and spare parts which are enforceable in one jurisdiction may not be enforceable in another jurisdiction”.

“The problem is obviously that any engine will sooner or later be attached to an aircraft and that restrictions in that respect may be commercially unacceptable”.

“It is noted that diligence is required not only when the engine lessee is a Dutch airline; if a non-Dutch engine lessee makes the engine available to an engine pool, it could well be that the engine ends up on the wing of a Dutch registered aircraft”.

“Fortunately, the Dutch legislator (sometimes) listens to what practitioners say [about aviation financing]”.

It is noted that all the comments, references, articles and documents that are cited in the present contribution are on file with the author.

From considering the above observations, the reader may appreciate that the application of the accession doctrine to the financing of aircraft engines is inappropriate. The legal uncertainty, which is created by this theory, leads to economic risk. This obstructs the availability of funds from the private sector and increases the cost of financing expensive engines. Moreover, due to the wrongful application of the Geneva Convention the acquisition of engines is hindered at the universal level. With this important conclusion in mind, it is difficult to envisage a Dutch or foreign Court applying the accretion principle in its quest for a justifiable ruling. Nevertheless, until today the same Dutch lawyers keep pushing this legal theory.

It is not surprising that many in the aviation community consider doing business in the Kingdom a risky enterprise. This conclusion is substantiated by the “black lists” which state that it is an “accession-risk” jurisdiction. For example, one of the largest aircraft and engine lessors in the world specifically refers to the alleged accretion risk in Aruba and the Netherlands in a memorandum:

“In certain jurisdictions, an aircraft engine affixed to an aircraft may become part of, or an ‘accession’ to, the aircraft, such that the ownership rights of the owner of the aircraft supersede the ownership rights of the owner of such aircraft engine. In such jurisdictions, if the owner of the aircraft has pledged the aircraft as security to a third-party, that third-party’s security interest may also supersede the ownership rights of the owner of the aircraft engine. This legal principle could limit […the…] ability to repossess an engine in the event of a lease default while the aircraft with the engine so installed, remains in such a jurisdiction. Countries whose Courts follow this interpretation as of the closing date include Aruba, […] the Netherlands […]”.

The cited document notes that Convention and Protocol over-ride the accession principle. It emphasizes, however, that these treaties have not been adopted by Aruba and the Netherlands. This article strongly opposes the conclusion of the aircraft and engine lessor that the Courts of Aruba and the Netherlands apply the accretion principle to aircraft engines. As is corroborated below, until today all the litigated engines disputes in these jurisdictions have clarified that no accretion of aircraft engines takes place. Moreover, it is anticipated that the Supreme Court will rule in the same direction.

Furthermore, the VP, Legal of a major aircraft lessor has expressed his concern about the alleged Dutch and international title-shift issue as follows:

“In summary, it could be said that neither treaty deals explicitly with transfer of title to engines by operation of law but that the Geneva Convention, which was never very widely adopted, in any event had no effect on such transfer whereas the provisions of the Cape Town Convention, which is growing in importance as it is increasingly adopted by more and more states, take precedence over any such transfer under national property law rules so long as the proper registration in respect of the international interest in the engine is made”. “It is to be hoped that this issue will fade away once the Netherlands becomes bound by the Cape Town Convention”.

To make the above deliberations complete, it is noted that the above-quoted Dutch critical comments have been published between 1992 and 2008. During this long period of time, in sophisticated jurisdictions the existing inadequate laws were adjusted to satisfy the contemporary requirements of a specific industry. According to the above citations, a desired change of the laws is also possible in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Thus, it is incomprehensible that during all these years the Dutch lawyers have undertaken remarkably little to change the alleged unacceptable aviation finance laws. What was their motive for not requesting the Dutch legislator to provide for a legal regime facilitating the acquisition and use of engines? Without any doubt, their initiative would have cured the depressions of their clientele.

The decisive rulings of the Supreme Court of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

In the international NDS Provider case, once more the Supreme Court of the Kingdom of the Netherlands had to fill the gaps that existed in the applicable commercial laws. See Supreme Court, (Hoge Raad), NDS Provider, C06/082, 2008, 177. The Court ruled explicitly that the draft provision of an international convention affirmed its line of reasoning. This international case concerned maritime tort laws. As the dispute was not solved by the text of the applicable law, the Court had to establish its goal and effects. In its quest for the proper law the Court explicitly applied the Draft UNCITRAL “Convention on the Contracts of the International Carriage of Goods Wholly or Partly by Sea”. In essence, in the NDS Provider ruling the Supreme Court confirmed that international treaties are the appropriate tools to interpret the goal of, and to fill the gaps in, the (ambiguous) laws. This rule is valid, regardless of whether the conventions are in force or have been ratified by the Netherlands.

This contribution appreciates that NDS Provider case concerned a liability in tort issue and not the separate financing of aircraft engines. However, the reasoning of the Supreme Court is pertinent in regard to the interpretation of the existing accession laws concerning engines and aircraft in the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It is submitted that the current international aviation finance regulations, whether or not they have been ratified, fill the gaps in the national laws.

The general Dutch law covering the financing of engines

The Supreme Court of the Kingdom had undertaken a similar legal research to establish the appropriate law in the landmark case concerning a tow-boat called Egbertha (Sleepboot Egbertha). See Supreme Court, 26 March 1936, NJ 1936, no. 757. The Court had to decide whether an engine that was installed in a tow-boat had legally become a component part of this ship. It judged that the prevailing view in a particular industry dictates whether a title-shift takes place. The Court ruled that the prevailing legal opinion considered an engine to be a part of the tow-boat. This view was expressed in a Dutch Royal Decree. A similar provision was contained in the “Convention concerning the recording of rights in inland vessels” (Geneva, 1930). It is noted that this instrument was not ratified by the Kingdom and it never entered into force. Nonetheless, the Court ruled that this treaty expressed the prevailing legal opinion that the engine acceded to the tow-boat. The reasoning of the Court is that treaties reflect the prevailing view existing in a specific international industry. The significant ruling of the Supreme Court in the tow-boat Egbertha case has been codified in the general accession laws of the Kingdom. These state that the prevailing view decides whether a movable object is considered to be a component part of another movable asset. In addition, an object that is affixed to the main asset in such a manner that it cannot be detached without substantially damaging either object becomes a part of the principal asset.

The problem concerning the alleged Dutch accession of aircraft engines

Article 8:3a(2) of the Civil Code of the Netherlands, Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles addresses the accession of aircraft engines to aircraft:

“The airframe, engines, propellers, radio apparatus, and all other goods intended for use in or on the machine “(toestel)”, regardless whether installed therein or temporarily separated there from, are a component part “(bestanddeel)” of the aircraft”.

This special law establishes that the aircraft includes its engines, contingent upon the requirement that these objects are “intended for use” in the machine (aircraft). The sole requirement for a potential title-shift is that an engine is destined for use in a specific machine. If an engine is intended for use in any aircraft it is not a component part. However, in the (unlikely) event that the legal qualification of a component part is established, this fact does not change when the engine is temporarily detached for a repair. There is no other differentiating criterion, as a “mechanical connection” between the engine and aircraft is not required. See the Dutch Governmental Explanatory Memorandum 1955-1956, no. 4134, p. 9.

The above-quoted Dutch lawyers suggesting that the accession doctrine is applicable, base their view only on the alleged requirement of the connection between the aircraft and the engine. They suggest that the installation decides whether an engine becomes a component part. At the same time, however, one of the strongest supporters of this view has said:

“Engines are [under Dutch law and the Geneva Convention] independent movable things […] as long as they are not installed on an aircraft and can therefore, in principle, be pledged. I say in principle because an engine may already lose its independent status before instalment to the aircraft”. “So if we would have a one-aircraft-operator having a spare engine on the shelf, one could argue that [under article XVI of the Geneva Convention] this engine is ‘intended for use in that aircraft’ and consequently part of that aircraft”.

The current contribution agrees with these comments, as the decisive requirement of the intended use of an engine in “that” specific aircraft is most clear. An attachment is not required to decide whether an engine is, or is not, a component part. The same Dutch lawyer has persisted in other publications, however, that the only criteria for the title-shift is the instalment. It is evident that this devoted proponent of the accession doctrine contradicts himself. Further consideration, therefore, need not be given to the erroneous interpretation of the Dutch laws and the relevant provision of the Geneva Convention.

Nevertheless, the text of the special Dutch law does not clarify whether an engine can be intended for use in a specific aircraft per se. As almost all engines are used in a flexible manner, can they become component parts of an aircraft at all? The above-cited law does not answer these questions. Accordingly, this gap must be filled by the general accession law which states that the prevailing opinion of the relevant industry decides whether a title-shift occurs. The Supreme Court ruled in the NDS Provider and tow-boat Egbertha cases that the international conventions, regardless of whether they have been ratified by the Kingdom or not, are workable tools to fill the gaps in the applicable laws.

The Cape Town Convention applies in the Kingdom

The only existing aviation finance regimes providing for uniform property laws are the Cape Town Convention and Protocol. Keeping the reasoning of the Supreme Court in mind, these instruments express the prevailing legal opinion of the international aviation practice that no accession of aircraft engines takes place. They are distinct aircraft objects which can be financed separately. The international interests which are created in engines can be registered in the International Registry. Considering the Court’s view that international treaties clarify legal uncertainties, regardless of whether or not they have been ratified, it is anticipated that the Convention and Protocol will support its conclusion that engines are not component parts of aircraft.

The alleged accession of aircraft engines initiated important court cases in Aruba and the Netherlands. In 2003 the Court of First Instance of Aruba judged that the accession laws do not apply to engines that are attached to aircraft. See Volvo Aero Leasing/AVIA Air, June 25, 2003, no. 121. The Court decided that it cannot be validly argued that the leading prevailing view of the aviation industry determines that engines are component parts of aircraft.

In 2002 the Court of Appeal in Den Bosch, the Netherlands, ruled in the same way as the Court in Aruba. In the AAR Aircraft & Engine Group/Aerowings case it had to decide whether the accession theory was applicable to a leased aircraft engine. See Court of Appeal (Hof) Den Bosch, 15 August 2002, SES, 2003, no. 56. The foreign lessor intended to repossess its engine from the Netherlands. The Court concluded that under the applicable English law no title-shift occurred. In addition, the Court reasoned that if Dutch property law would have been applicable, no accession would have taken place. To a large extent the Court based its decision on the following particulars. The legal department of the Dutch airline KLM had provided the Court with a letter addressing the alleged accretion of engines. It stated that the lessors assume that engines will not accede to aircraft. According to KLM, the international prevailing view in the aviation sector concurred in this respect. Moreover, KLM declared that the title-shift theory would endanger the possibility of leasing engines at the global level. Based on this pertinent information the Court ruled that the prevailing opinion of the aviation finance industry clarified that engines are not component parts of aircraft. It is stressed that until today the outcome of all the litigated engines disputes in the Kingdom has been that no accession of engines occurs.

Some concluding remarks

This article neither agrees with some Dutch lawyers that the doctrine of accession applies to aircraft engines in the Kingdom, nor concurs with their suggestion that the Geneva Convention validates this theory. To the contrary, these aviation regulations are designed to facilitate the efficient financing of aircraft and engines. More precisely, these laws are aimed at streamlining the global acquisition and use of aircraft equipment. On the other hand, it is primarily the erroneous Dutch interpretation of these rules that frustrates these transactions. The lower Courts in the Kingdom concur with this view. While the Cape Town Convention and Aircraft Equipment Protocol decide that no accession of engines takes place, these instruments have not yet been ratified by the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Considering the Supreme Court’s view that international regulations are tools to clarify legal uncertainties, regardless of whether these treaties are in force or not, it is anticipated that the Convention and Protocol apply in this jurisdiction. They establish that no title-transfer of engines occurs when they are connected to airframes.

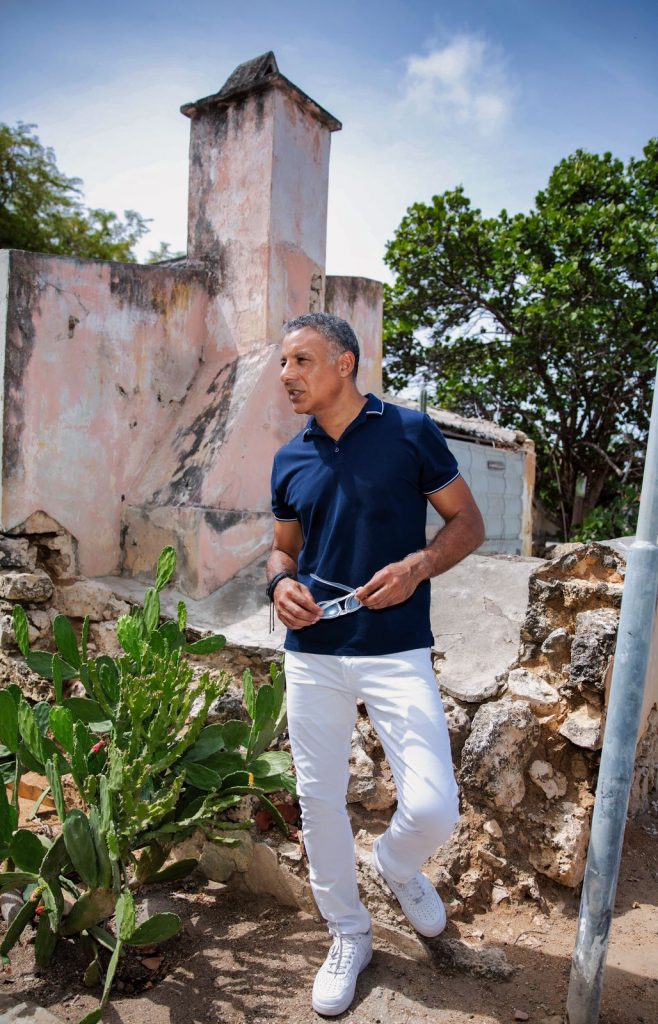

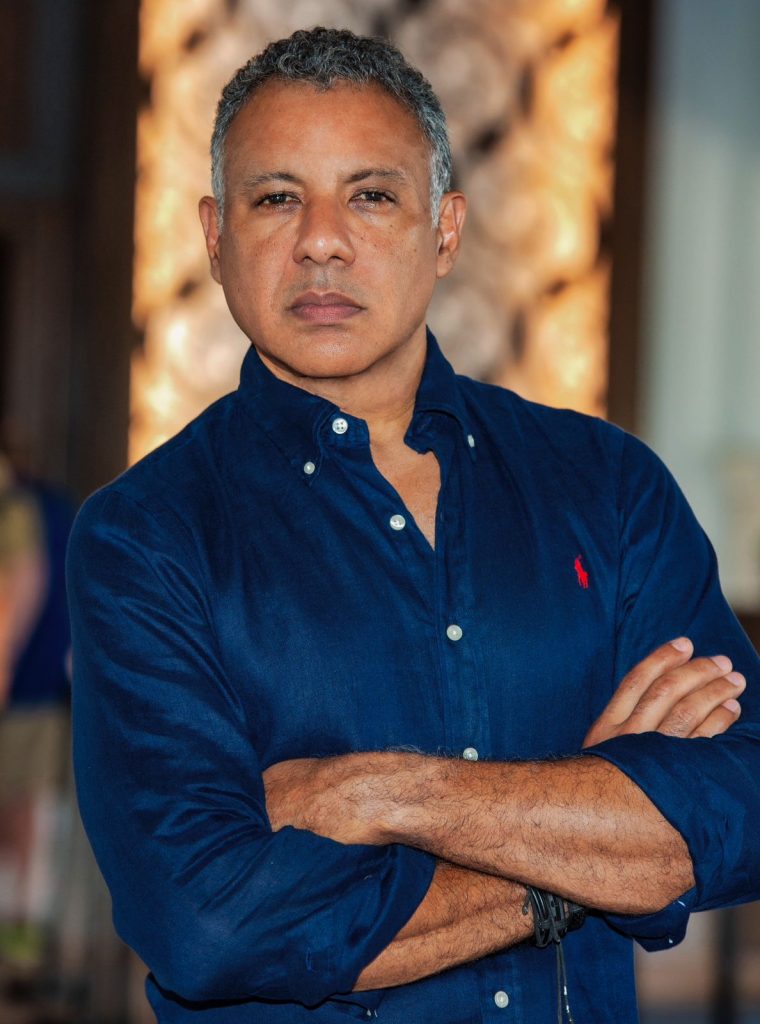

Patrick Honnebier is counsel for Gomez & Bikker, aviation law offices, in Amsterdam-Aruba. He is a lecturer in international aviation finance law and international institute air and space law at the University of Leiden and VP legal, Hastings & Huang, traders of aviation and other fuel supplies, Singapore. E:[email protected]

Definition of accession: “Accession (from Lat. accedere, to go to, to approach), in law, a method of acquiring property adopted from Roman law (see: accessio), by which, in things that have a close connection with or dependence on one another, the property of the principal draws after it the property of the accessory, according to the principle, accessio cedet principali”